Social media companies have long come under fire for the content that appears on their platforms, ranging from the fake news that proliferated on Twitter during the 2016 US presidential election to the hate speech that seems to always find a home on Facebook, leading at least 1,000 advertisers to boycott the platform in 2020.

Most recently, Spotify found itself in hot water over its decision to pay hundreds of millions of dollars for exclusive content from famous podcast content creators accused of spreading misinformation. We revisited the company’s podcast strategy last week as a means of better understanding this current controversy, which raises larger questions about Spotify’s role in the ecosystem.

What exactly is Spotify? When asked directly if it is a tech company with a media business or a media company with a tech platform, here’s how Dawn Ostroff, Spotify’s chief content and advertising business officer, responded:

Can Spotify — or any platform — really be both?

A neutral player?

Whenever there is confusion over content that appears on a platform, a few things typically happen. The platform will often frame the issue as one of free speech, and someone will inevitably bring up Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which shields internet platforms from liability over third-party content. But the free speech discussion is largely a waste of time here.

What this really comes to is that platforms are trying to have their cake and eat it too. They want to be perceived as simple, neutral distribution networks for content and products, but at the same time, they are acting as publishers and/or media companies by curating and promoting specific content, whether it’s Spotify with Joe Rogan, Substack with various authors, or – lest you think this is limited to media – Amazon with the Amazon Marketplace.

Claiming to be a neutral distribution mechanism without control over the content being distributed is critical for platforms that distribute user-generated content. If terrorist propaganda is uploaded to, say, YouTube, the platform can choose to take it down or to do nothing. Since YouTube is not producing or curating this content, it is off the hook. Traditional media owners don’t enjoy the same type of protection.

Here is where things get murky. Although platforms may want to claim neutrality, many are more than dabbling in content creation. And if it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it’s not a platypus, as some would have us believe.

For Spotify — the platform problem child of the current news cycle — this is what the challenge boils down to: It became a media owner when it started buying specific content players, including The Ringer (the Bill Simmons podcast network), Gimlet Media (a podcast producer), and the exclusive rights to distribute Joe Rogan’s content. It can no longer claim neutrality — because it is no longer neutral.

A fundamental conflict

Other platforms face a variant of the same challenge. Consider Amazon and its AmazonBasics product line. When Amazon owns, creates, and distributes its private label products in its marketplace, where they're competing with other non-Amazon brands, it can tailor user search results to prioritize its own products. We have a similar concept in retail, where companies across the spectrum routinely hawk their own private labels. But those retailers also have agreements with different brands on considerations like shelf placement, which is different from the digital realm, where information asymmetry gives platforms the opportunity to opaquely boost their own interests.

We’ve long discussed how the US relies on antiquated legal frameworks to regulate Big Tech. New legislation has been introduced to reform outdated antitrust laws, curb the platforms' monopoly power, and reduce conflicts of interest. But a general laissez-faire attitude from US regulators during the development of the internet led to rapid acceleration and innovation. As platforms grew, becoming too big to fail, regulators were essentially asleep at the wheel. Now the largest tech platforms are so dominant that their revenue exceeds the gross domestic product of many relatively large countries.

They're also starting to challenge the core tenants of how we consume content, transact online, etc. We don't have a good response as a country for the misaligned incentives that benefit the platforms — at the expense of smaller challengers.

A path forward?

Other countries, however, have an opportunity to head off that scenario, but it's also somewhat antagonistic because many of the largest platforms now wielding outsize influence were founded in the US. European regulators that watched US-based platforms siphon revenue from formerly healthy local news and commerce ecosystems over the years may be more willing to take on the platforms, and they’ll get a lot of local support. But that may not be the answer.

One approach that has immediate potential is a proposal introduced in India that would allow companies to either operate a marketplace or sell their products in the marketplace, but not both. One of the reasons why we like this approach is because it effectively eliminates a major point of overlap. You’re either a platform or a content owner. If a platform wants to invest in content, that content can't be distributed on its platform if it wants the protections of a neutral platform.

Is the solution to spin off a platform’s content creation arm? Maybe. There really is no easy button here that would eliminate these conflicts of interest. Since there is no appropriate regulatory framework, we're all winging it.

Where is the customer in all of this?

In the absence of proper controls, other interesting questions emerge, especially when platforms expand into other industries. Most significantly, who owns customer experience?

If the long-term argument is that we should give all of our data to platforms because they provide a good customer experience, that tradeoff still largely makes sense for users. We personally don't mind being permanently signed into Google because Google gives us, say, Maps for free — and that provides a lot of customer-facing utility.

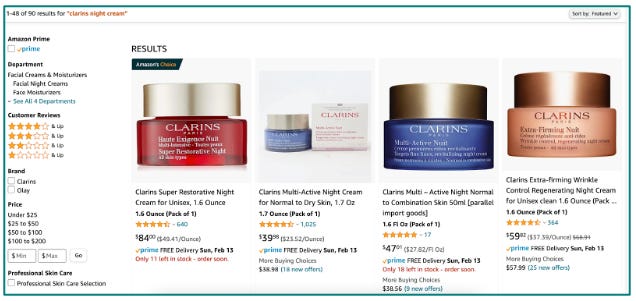

But if a platform is self-dealing, can it maintain the same level of customer experience that customers will continue to find valuable? Say a consumer wants to buy Clarins Night Cream on Amazon. When they look for this product on the platform, they may find a few different options for their desired night cream without realizing that they may be ordering the cream from a third-party seller, not directly from the brand. If the buyer receives a fake product, they are likely to voice their discontent with the brand — not with the platform or the third-party seller — and brands may be blissfully unaware of the depth of this challenge.

Same goes for Spotify. Is its recommendations algorithm surfacing cool new podcasts or music based purely on a listener’s interests or will it stealthily prioritize Spotify artists or other creators that provide a higher margin for the platform? Apply this across a global user base of more than 400 million, and it can quickly add up.

Google’s recently unredacted antitrust lawsuit shed light on similar practices where Google’s control of every piece of the online ad delivery ecosystem allowed it to operate opaquely. It secretly prioritized its own interests to the detriment of its customers: publishers and advertisers.

These are not siloed challenges — they are fundamental challenges of a platform in this day and age. There may be slightly different manifestations depending on which platform we’re discussing, but this comes down to a few basic questions for companies. What are their lines of business? If they control competing lines of business, can they still claim neutrality? Or should we think of today’s platforms as media companies that must play by slightly different rules — or as some other type of entity that we haven't defined yet?

One question

When you search for ‘Clarins night cream’ on Amazon, which of these row 1 search results is the brand’s store vs. a third-party marketplace seller?

(Spoiler alert: none!)

Dig deeper

India’s tighter e-commerce rules

Proposed US platform antitrust legislation

Thanks for reading,

Ana, Maja, and the Sparrow team

Enjoyed this piece? Share it, like it, and send us comments (you can reply to this email).

Who we are: Sparrow Advisers

We’re a results oriented management consultancy bringing deep operational expertise to solve strategic and tactical objectives of companies in and around the ad tech and mar tech space.

Our unique perspective rooted deeply in AdTech, MarTech, SaaS, media, entertainment, commerce, software, technology, and services allows us to accelerate your business from strategy to day-to-day execution.

Founded in 2015 by Ana and Maja Milicevic, principals & industry veterans who combined their product, strategy, sales, marketing, and company scaling chops and built the type of consultancy they wish existed when they were in operational roles at industry-leading adtech, martech, and software companies. Now a global team, Sparrow Advisers help solve the most pressing commercial challenges and connect all the necessary dots across people, process, and technology to simplify paths to revenue from strategic vision down to execution. We believe that expertise with fast-changing, emerging technologies at the crossroads of media, technology, creativity, innovation, and commerce are a differentiator and that every company should have access to wise Sherpas who’ve solved complex cross-sectional problems before. Contact us here.