Revisiting Google’s DoubleClick Acquisition

Quick, to the time machine!

A week before most of the advertising industry gathered at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity—where Google is a big sponsor—)the European Commission initiated formal antitrust proceedings against the company and called for a breakup of its digital ad business. Regulators say Google breached antitrust rules by using its ad buying and ad serving tools to favor its ad exchange at the expense of other exchanges, publishers, and advertisers. A mandatory divestment, the EU says, is the only way to address these concerns.

Antitrust pressure has been mounting on Google for years. The bloc has already fined Google more than $8 billion for assorted antitrust violations. The EU began probing Google’s ad tech business in 2021, and it is also facing an investigation in the UK. In the US, the Department of Justice sued Google in late 2020 for anticompetitive practices in search advertising. The DOJ and several states have also sued the company for violating antitrust laws in its digital advertising business. The DOJ is pushing for Google to sell Ad Manager, its product suite that includes its ad exchange and ad server.

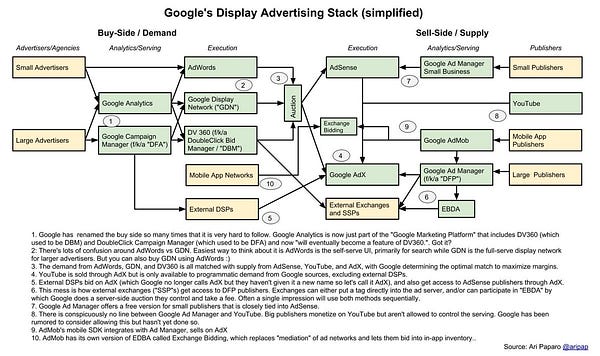

At issue is how Google controls key parts of the digital ad supply chain to give itself an advantage. It operates two tools used by advertisers to buy ads (Google Ads and DV 360); an ad server used by publishers to distribute online ads (DoubleClick For Publishers); and an ad exchange where advertisers and publishers buy and sell ads through auctions (AdX).

In December 2020, we explored five scenarios that could have happened if Google had never acquired DoubleClick. The pivotal 2007 deal laid the groundwork for its outsize influence in digital advertising.

Knowing what we know now, would Google's DoubleClick acquisition have cleared regulatory hurdles if it happened today?

Let’s revisit one of our favorite ‘what ifs’: what if Google never acquired DoubleClick?

In October 2020, following years of not-if-but-when speculation, the US Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google alleging exclusionary practices in search advertising, where, per eMarketer projections, Google currently owns ~58% of US market share. Beyond search, Google commands 29.4% of the entire US digital advertising market and attributes 70% of its $162 billion global topline revenue to advertising.

This perilous yet vaunted position in which Google finds itself has been more than a decade in the making. The pivotal acquisition that set Google on its path toward global advertising domination occurred back in 2007, when Google ponied up $3.1 billion in cash to buy NYC-based DoubleClick.

Digital advertising in 2007 was a nascent discipline: The IAB/PwC annual internet advertising report pegged the value of all of US digital display advertising at $5 billion. Advertising sales were relationship-driven and quite manual in nature – lots of phone calls, fancy dinners, and networking events made insertion orders move. The three key players in search – Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft – were all expanding aggressively into display. And all three were interested in DoubleClick for different reasons.

Yahoo was rapidly losing search market share and, under Terry Semel’s leadership, seemed to be trying to shed its tech company roots in favor of being perceived as a media company. Despite its identity crisis, Yahoo's homepage was a must-buy for large campaigns and Yahoo’s display assets were growing handsomely. An effective direct sales team brought in revenue while the company worked to figure out how to monetize remnant inventory in efficient ways (an area where DoubleClick could have certainly helped and was later addressed by its RightMedia acquisition). Microsoft (and MSN) was also a must-buy for advertisers. The software company was used to selling to enterprise clients, so adding DoubleClick’s suite of tools for enterprise-tier advertisers and large media companies would have been right on the mark. There was also a potential defensive angle of DoubleClick off the market to slow Google’s growth in display.

Google had indeed been growing quite aggressively, but it lacked direct relationships with advertisers. Without those relationships, its growth in display would have been limited and, short of acquisitions, that’s not an easy capability to enable overnight.

In the end, Google won a competitive auction for DoubleClick, and the rest, as they say, is history. The DoubleClick acquisition instantly positioned Google as a leader in both search and display, and it prevented its key search competitors at the time from gaining a better foothold in the emerging display category.

But *what if* that acquisition had never happened? Here are 5 scenarios worth considering in this episode of ad tech’s alt-history.

1. Could DoubleClick have remained independent?

While DoubleClick is primarily thought of as an ad server, it had four different product lines at the time of acquisition: publisher ad server (DART for Publishers, aka DFP), advertiser ad server (DART for Advertisers, aka DFA), several search and data services products mainly based on DoubleClick’s acquisition of Performics, and the just-released DoubleClick Advertising Exchange.Its biggest assets were strong relationships with advertisers, agencies, and publishers. Doubling down on pure-play independent ad tech for the world’s largest publishers and advertisers would have been the way to go, but few companies at the time thought of their digital ad servers as truly strategic assets. With private equity ownership, the onus to sell was undoubtedly high; if not Google, then the other two bidders – Yahoo and Microsoft – as well as AOL and telcos would all likely have been in play as strategic acquirers. Had DoubleClick remained independent, it would have likely faced immediate pressure from Google, which has a tendency to offer ad tech tools for free in order to quickly lock up a market. (Consider how the release of Google’s free Tag Manager product essentially obliterated a rather vibrant tag management category in 2012).

Microsoft would go on to buy DoubleClick competitor Atlas/aQuantive in 2007 for $6.3 billion in cash. The acquisition didn’t provide the same benefits to Microsoft as DoubleClick provided for Google: Microsoft took a $6.2 billion write-down, and it sold off the Atlas piece to Facebook in 2013 for close to $50 million, according to news reports. While that didn’t have a happy ending either, Microsoft didn’t lose much in the long term. (The same cannot be said for Yahoo.)

2. What would Google’s ad business look like today?

Google was already making inroads into display prior to its Doubleclick acquisition, but unlike search, display was more high-touch. On the product side, Google would have likely built a competitive set of ad servers, similar to how Facebook built its own tech. What Google didn’t have were the relationships that would put those ad servers to good use (even if they were free). Choosing a different ad server (such as 24/7 RealMedia’s OAS, which WPP bought in a reactionary move following the DoubleClick acquisition) would have also made sense for Google, as long as the goal was explicitly to touch both the buy and sell sides. The most likely outcome would have been much slower growth and, in case either Yahoo or Microsoft bought DoubleClick and executed well, a potential reversal of fortunes and loss of market share on the search side. In other words, today’s Google could have been Yahoo.

As attractive as DoubleClick was, arguably the biggest value-add wasn’t the tech, which is a somewhat ironic realization for one of ad tech’s most pivotal acquisitions. DoubleClick also solidified Google as a strategic ad tech acquirer. The experience of integrating such a big, formerly public company into Google’s culture and the footprint it was able to create in New York set up Google favorably for subsequent activity (not to mention the mountains of cash it have been able to so reliably generate every year). To date, DoubleClick remains Google’s third-largest acquisition, preceded solely by Motorola Mobility in 2011 for $12.5 billion and Nest Labs in 2014 for $3.2 billion. Without DoubleClick, perhaps its appetite for subsequent ad tech acquisitions would have been much more tempered.

Instead, Google’s subsequent ad tech deals gave Google the “building blocks” needed to play at every step of the online ad sales process. “Google has put it all together,” Jeffrey Rayport, an online marketing expert at the Harvard Business School, told The New York Times. “Google is the market under one roof.”

3. Would large publishers embrace a homegrown Google stack?

We won’t belabor Google’s track record with publisher relationships, but let’s assume that Google was able to cultivate those through the tail end of the 00s. Migrating ad servers is hard: For many large publishers, the layers of built-in custom logic crammed into their ad servers over time would have made ad ops and IT departments cringe at the very thought of replacing. Sticking with DoubleClick over adopting a new stack would have seemed like the better option for most publishers (not counting the nuclear scenario in which Google builds its own ad server and offers it for free).

Today, Google also competes with publishers via YouTube and assorted other efforts (e.g., AMP, expanded SERPs, etc) that affect traffic to individual sites. Few major publishers seem to care about this; perhaps the best illustration isDisney’s recent move away from Freewheel and onto Google, arguably its biggest competitor.

The most likely scenario here would have been Google investing in alternative ad formats only available through its own stack and a likely stratification of ad tech stacks at the top of the market. If publishers were to have embraced the Google stack sans DoubleClick, its homegrown offering would have likely prioritized APIs and custom, modular builds (similar to how Amazon Web Services goes to market or the Adzerk/Kevel model). For Google, being a tech company, this approach makes sense and plays to its strengths and depth of expertise in engineering.

4. What’s the impact on the NYC tech ecosystem?

In 2007 the NYC tech ecosystem hadn’t yet fully arrived. Silicon Valley was where tech happened; New York had many other industries going for it, but tech had yet to have its marquee exit. While your sales, client success, and marketing teams were in Manhattan, your engineers were likely somewhere on the West Coast. If you wanted to raise venture capital, you had to hop on a plane and hit up Sand Hill Road. A popular choice among ad tech’s scrappy founders was the double red-eye special: take the first plane to San Francisco, pitch all afternoon, stay for dinner, and hop on the red eye back to NYC. (What a terrible idea.) It seems silly in retrospect, but New York hadn’t yet experienced any billion-dollar-plus tech acquisitions. But the DoubleClick acquisition announced to the world that the NYC tech ecosystem was alive, kicking, and ready for ambitious entrepreneurs – many of whom would emerge from the ranks of DoubleClick alumni. Nowadays, New York is one of the best places in the world to build a tech company – especially an ad tech one – and this would have likely taken a lot longer to achieve without DoubleClick.

5. Would Google without DoubleClick still raise the same regulatory concerns?

The focus of the Justice Department's current regulatory complaint mainly focuses on search, which is fascinating because it is perhaps the one piece of Google’s business that really couldn’t have been regulated as it was almost exclusively homegrown.

What regulators could have done was to more closely scrutinize or even deny approval of the DoubleClick deal. “If I knew in 2007 what I know now, I would have voted to challenge the DoubleClick acquisition,” former FTC commissioner William Kovacic told the New York Times earlier this year. Instead, he and three other commissioners voted to approve the acquisition, despite industry experts sounding the antitrust alarm at the time. Google had a market cap greater than any of its competitors by the end of 2007, so even if it were unable to acquire DoubleClick, there is likely little that would have stopped Google from acquiring another competitor or building its own products before engaging in its MO: offering a product for free to grab market share. Yet the Justice Department’s lawsuit – or any current lawsuit – is unlikely to directly attempt to undo the portions of Google’s stack that originated as DoubleClick.

There’s also a larger point to consider: Google is so large and interconnected that looking at any single ad revenue line of business may not be enough to address regulators’ concerns. Beeswax CEO (and former Googler) Ari Paparo sketched out the reference map that illustrates the underlying complexity:

One question

How will this era of heightened antitrust scrutiny affect other Big Tech deals, particularly Microsoft's proposed acquisition of video game giant Blizzard Activision?

Dig deeper

EU's statement of objections to Google over abusive practices in online advertising technology

DOJ Sues Google for Monopolizing Digital Advertising Technologies

Thanks for reading,

Ana, Maja, and the Sparrow team

Enjoyed this piece? Share it, like it, and send us comments (you can reply to this email).

Who we are: Sparrow Advisers

We’re a results oriented management consultancy bringing deep operational expertise to solve strategic and tactical objectives of companies in and around the ad tech and mar tech space.

Our unique perspective rooted deeply in AdTech, MarTech, SaaS, media, entertainment, commerce, software, technology, and services allows us to accelerate your business from strategy to day-to-day execution.

Founded in 2015 by Ana and Maja Milicevic, principals & industry veterans who combined their product, strategy, sales, marketing, and company scaling chops and built the type of consultancy they wish existed when they were in operational roles at industry-leading adtech, martech, and software companies. Now a global team, Sparrow Advisers help solve the most pressing commercial challenges and connect all the necessary dots across people, process, and technology to simplify paths to revenue from strategic vision down to execution. We believe that expertise with fast-changing, emerging technologies at the crossroads of media, technology, creativity, innovation, and commerce are a differentiator and that every company should have access to wise Sherpas who’ve solved complex cross-sectional problems before. Contact us here.