Media businesses used to have a simple formula: Grow the number of subscribers, readers, viewers, etc. reliably and you’ll grow your advertising revenue equally reliably. The relationship between audience size and additional revenue was linear and very dependable: The larger your audience, the more advertising revenue you generate. Digital media for a while stuck to this formula – hence everyone’s incessant focus on audience size and scale – but the platform era made that equation obsolete. Thanks to Facebook, Google, and friends, even the most prominent global publishers look puny compared to platforms’ daily active users, reach, or any other metric of media relevance. It’s no longer enough for a publisher to have an audience; they must also have the right type of audience to stay in business.

In that quest for scale, media companies naturally embraced M&A. On paper or a spreadsheet, it’s easy to justify that a larger combined audience and potential streamlining of content production can generate more favorable business outcomes for everyone involved. The reality of post-merger execution, however, is often quite different. The AOL-Time Warner merger back in 2001 often features prominently on “worst merger of all time” types of lists; it took 20 years and many interim iterations to untangle, finally sputtering out with Apollo-Yahoo in September 2021. Then there’s the ongoing decimation of national, regional, and local mastheads and newsrooms: Faced with no longer sustainable business models, these formerly revered media entities are prime targets for rollups and sell-for-scraps outfits.

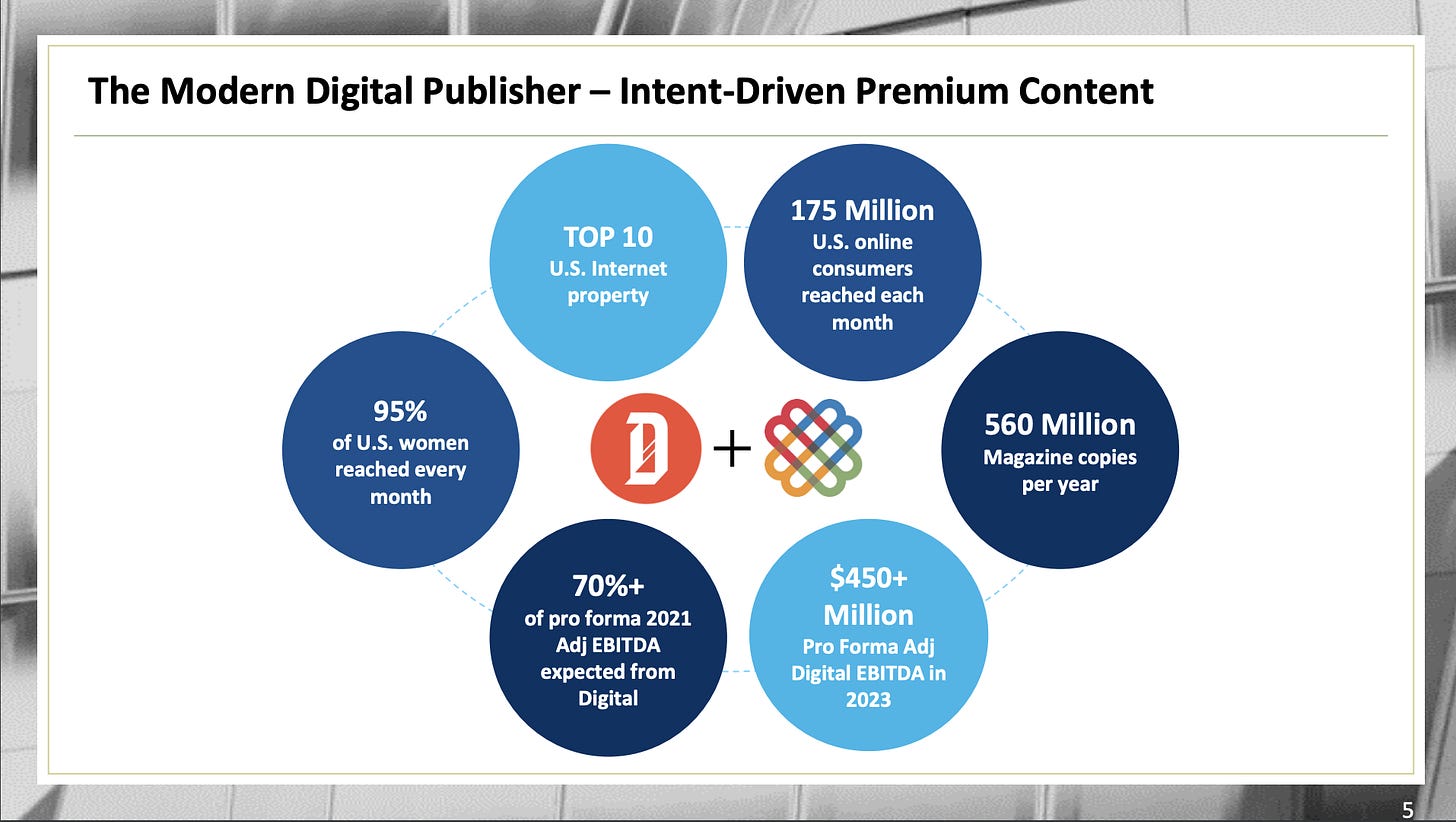

Yet, when news broke that Dotdash is buying Meredith, a new sign of hope for older media appeared on the horizon. A decade ago, it would have probably been Meredith doing the buying. As media mergers go, this one almost seems modest: For $2.7 billion, Dotdash is nearly doubling its user base, reaching a whopping 95% of all US women.

How a digitally native publisher can absorb a traditional publisher like Meredith*

What makes Dotdash such an outlier in a mainly bleak field of publishers? Where others have needed to sacrifice user experience for the sake of monetization, Dotdash has aggressively pivoted to quality. (What a concept!) By focusing on a smaller number of verticals, improving reader experience, and providing fewer but more valuable, easily bought ads, Dotdash has created quite a lucrative niche for itself and presents a viable, brand-safe alternative to platforms for advertisers interested in targeting lifestyle content.

This is a merger of audiences and business models perhaps best illustrated by this slide, which shows the companies’ respective lines of revenue are almost perfectly complementary:

Near symmetry *

We’ve been fans of Dotdash’s approach for a while. Almost exactly a year ago, we wrote about what makes its approach so interesting – and it remains one of the most-read Sparrow Ones to date. Let’s revisit, with a 2021 refresh.

“... there is no business in gaming someone else’s algorithm in the long term. It’s been proven over and over and over and over again.”

—Neil Vogel, “Recode Media with Peter Kafka,” 2019

Dotdash was flying high in January 2019 when Neil Vogel joined Recode’s Peter Kafka to talk about the media company’s evolution from faded internet giant to one of the darlings of parent company IAC’s portfolio. Dotdash’s annual revenue had increased 44% compared to the year before, and total unique visitors to its properties had reached 87 million – up from 51 million uniques from before it was rebranded from About.com.

The media company is still cruising after seemingly defying the coronavirus pandemic and economic carnage left in its wake. While Dotdash’s 2020 revenue growth slowed, it has since returned to form. In the first half of 2021, Dotdash's total revenue increased by some 56%. That strong revenue growth, combined with healthy margins, led half a dozen analysts to recently value DotDash at just over $1.9 billion.

While most publishers continue to struggle with economic headwinds and the realities of changing business models, there are a few exceptions that seem to buck the universal doom, gloom, and malaise. There’s the news property Axios, for example, the revamped under-new-ownership Time magazine, the punchy Business Insider, and emerging formats such as paid newsletters that fundamentally present a different content production calculation.

And then there is Dotdash. The publisher’s intent-based audience strategy evaded the catastrophic advertising revenue declines that struck almost every other publisher during the pandemic. The company provides a compelling lesson for other publishers, many of which follow the tortured path originally articulated by Rita Mae Wilson and often misattributed to Albert Einstein:

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results.”

Instead, the Dotdash rebrand and strategy offers a simple formula for a new type of media company that can withstand and even thrive in unpredictable environments.

And the company keeps executing that plan without fail. It doesn’t do subscriptions, which many publishers began desperately testing during the pandemic. And Dotdash doesn’t publish news, so it avoided much of the advertiser flight we saw last year from hard news such as the coronavirus and social unrest. It wasn’t completely immune to the headwinds; it experienced firsthand the decline in traveling advertising dollars, but it was able to offset those losses by its diverse range of media properties, which represented safe havens for advertisers during the pandemic.

And now for some history on a critical pivot

Dotdash’s success, however, was far from assured; in fact, it was one of the biggest mastheads of the early internet era and seemed destined for the forgotten low-quality content heap, joining the likes of Demand Media and other content farms that profited from the gaming of Google’s algorithm.

Founded in 1997 by digital media guru Scott Kurnit, the site that would become About.com was initially designed to cover a ridiculous number of topics. The company changed hands several times, first to Primedia in 2000, and then to The New York Times five years later. Though it had always been profitable, the Great Recession, Google’s algorithm changes, and the emergence of Facebook took a toll on digital media, leading the Times to sell About.com in 2012 for $300 million to Barry Diller’s InterActive Corp (IAC), whose properties include Care.com, The Daily Beast, Angie’s List, and the Match Group of dating brands, which was spun off in June 2020.

IAC gave About.com autonomy, patience – a rare gift for a public company – and Neil Vogel, who was named CEO in 2013 and rebuilt the site’s technology and redesigned its content. The company persisted and remained profitable, but it stopped growing and, instead, its audience shrank.

“Users would get to our site and didn’t know what to make of us,” Vogel told AdExchanger’s Kelly Liyakasa in 2016. “It’s hard to get a fried chicken recipe from the same people who have ‘how to treat colitis’ content, no matter how good the content is. And advertisers loved our scale, reach, and data, but if it was between us and Everyday Health, it wasn’t a fair fight.”

Vogel and his team saw that the publishers that were succeeding were vertical, premium publishers. In 2016, About.com stopped trying to be all things to all people and began launching vertical sites with unique branding and dedicated teams, including Verywell (health and fitness), The Balance (personal finance), Lifewire (technology), The Spruce (home and food) and ThoughtCo (learning). About.com officially became Dotdash in 2017, launching TripSavvy (travel) a few weeks later.

While About.com was never a content farm, per se, much of its content was old, not all of it great. Its new strategy banked on “need to know publishing” – high-quality evergreen content that could answer readers’ questions, solve their problems, and provide inspiration. It employed about 125 editorial employees and used about 1,500 freelance writers as of December 2019, according to one pitch deck. Every piece of content is updated at least every year, and sometimes even every week.

To achieve its vision, the company created long-term plans, with short- and medium-term results. The company developed a clear process for launching a new brand or vertical, including a three-month incubation period followed by expected revenue in the fourth month. For example, Dotdash acquired Simply Recipes and Serious Eats in September 2020, so based on its acquisition playbook, the properties should have begun generating revenue for Dotdash in January 2021. It also closely guards its first-party data and strictly locks down its audience, so advertisers can only buy its inventory from Dotdash. The publisher has also supplemented its advertising with affiliate commerce, performance marketing, and consumer revenue.

“This transformation led to something extraordinary in digital media – a turnaround,” Aaron Cohen wrote in Fast Company in January 2020. “While other independent media companies were engineering their coverage around social media, video, and trending topics, Dotdash doubled down on text-based articles about enduring topics and avoided cluttering them with ads – a strategy that Daniel Kurnos, an analyst at the investment bank Benchmark, credits with boosting Dotdash content in search results. (He calls IAC an ‘algorithmically elite’ company for its deep understanding of how to infiltrate search engines.)”

Turns out that “pivot to video” wasn’t the only strategy available.

Dotdash has demonstrated the potency of high-quality brands and content combined with intent-driven audiences. Fewer, better ads are a key component of more reliable advertising monetization for the publisher.

Four key differentiators:

Ads:

When most publishers were stuffing their pages full of ads to juice revenue, Dotdash chose to focus on a better user experience, with 35% fewer ads, which serves to declutter pages and speed up the sites; the ad units are also more impactful, with no pop-ups or interstitials. Though there are fewer ads, they command higher CPMs. All of its ads, including high-impact, home page, and native, are available to advertisers programmatically, according to Sara Badler, Dotdash CRO, enterprise advertising and partnerships.

Dotdash expanded further into online beauty advertising through acquisitions of cross-vertical properties Byrdie, Brides, and MyDomaine – a lucrative category dominated by incumbent publishers such as Condé Nast and Hearst. With the purchase of Meredith properties, Dotdash is adding powerhouse brands in its existing verticals and opening up one new vertical: entertainment. It’s rare in media to see someone 1) have a strategy and 2) be able to so consistently execute on that strategy over time. Here, Mr. Vogel’s team stands head and shoulders above everyone else even trying to compete, and peers would do well to study, emulate, and replicate Dotdash’s success.

But while advertising represents the majority of Dotdash revenue today, the company is also aggressively diversifying with e-commerce plays and branded merchandise, such as pet care products and paint; in 2019, e-commerce accounted for roughly 25% of Dotdash’s revenue, so there was/is plenty of room for growth.

Programmatic strategy and buying options:

Dotdash has made it easy for advertisers to buy its inventory directly and programmatically. The company has embraced programmatic ad buying and is known to help advertisers make their buys more efficient with private marketplace deals (PMPs), which may include price controls, and supply-path optimization, which identifies the most effective path to its inventory.

For Dotdash, “the role of the PMP has definitely evolved because, with supply-path optimization, we’re able to say these are the primary SSPs we use and this is the best way you can access our inventory,” Badler told Digiday in 2019. “It brings back the conversation of this is why the PMP is valuable, because you’re getting a direct connection into what we do and how we do it.”

The company takes a vertical-specific ad sales approach. It hired experienced sellers in each vertical and packages specific offerings for each. Dotdash concentrates on driving spend from key advertisers in each vertical. Ad revenue had been growing at a 19% compound annual growth rate, as of 2019 Q3, with more than 90% retention of its top 25 advertisers over the prior three quarters. It also works with advertisers to identify unique objectives and document what works as case studies to illustrate success and drive more business.

Exclusivity:

Dotdash emphasizes its first-party intent data over third-party data. Its audience is only available through Dotdash. Dotdash executives have articulated the uniqueness of its intent-based audiences in appearances at industry conferences and in the press.

Its first-party intent data, gleaned from the more than 100 million monthly users who visit its sites, often with specific questions they want answered, allows Dotdash to help marketers with targeting and measurement without the use of third-party cookies, which will be deprecated by Google Chrome within the next couple of years or so. For example, Dotdash once helped a financial marketer reach people who were consuming content about retirement planning and savings on Investopedia and The Balance. The publisher used that consumption behavior to create segments for the marketer that could be purchased programmatically. Badler said that the Dotdash intent data boosted the brand’s click-through rates by 50% relative to a non-targeted buy using third-party data. The segments cost more and varied in size because of seasonality, which Badler argued was justified by their performance. Dotdash can also help marketers with device-specific insights and identify differences in iOS and Android users, giving them the ability to cherry-pick only those they want to reach.

The publisher is positioned well for the impending loss of third-party cookies, which will impact targeted advertising and measurement.

“If every cookie disappears tomorrow, it would be great for us,” Vogel said during an AdMonster event. “We can map every piece of content to every other piece of content. We’ve been doing this so long, we know exactly how a campaign will perform as soon as we lock in.”

Niche vs. scale:

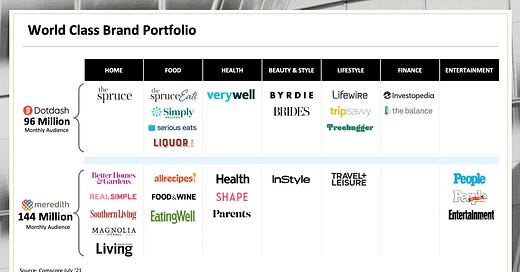

Dotdash has just enough scale: more than 100 million unique visitors across its sites. It is No. 36 on the Comscore Top 100, and Meredith is No. 15. The company continues to grow through acquisition and at the time of writing operates 14 properties:

Simply Recipes (acquired Sept. 2020)

Serious Eats (acquired Sept. 2020)

TreeHugger and Mother Nature Network (acquired Jan. 2020)

Liquor (acquired Sept. 2019)

Brides (acquired May 2019)

Byrdie (acquired Jan. 2019)

MyDomaine (acquired Jan. 2019)

Investopedia (acquired July 2018)

TripSavvy (launched June 2017)

ThoughtCo (launched March 2017)

The Spruce (launched March 2017)

Lifewire (launched Nov. 2016)

The Balance (launched Sept. 2016)

Verywell (launched May 2016)

With the Meredith acquisition, Dotdash is deepening each of these verticals and adding a new one. It becomes less niche vs. scale and more niche and scale.

Its acquisition plan typically involves buying service-oriented sites with loyal followings and heavily investing in them.

“It usually takes us three months or less to transition onto our tech stack,” Vogel told Digiday. “We take that three months and do deep dives on their content. We bring the editorial teams in and we understand what they want to do, what they’d do if they had unlimited resources. We spend three months hashing out content, then we get them on our platform. We are initially most concerned with the tech, the product, and the content, then we will figure out the revenue. To bring it to advertisers in the best way, we need it on our platform.”

Dotdash’s strategy also hits at the core of that niche vs. scale monetization challenge that modern publishers face. There’s little chance and even less sense in competing with the likes of Facebook and Google on scale; yet current monetization methods rarely work well for niche publishers that also need to maintain legacy (read: expensive) content production lines. This umbrella approach of niche brands that target similar verticals and audiences can work well and is certainly something we see as also emerging in other industries. (The best examples are challenger brands, which we first covered here.)

The takeaway

The Dotdash strategy seems so simple, and it’s been proven to not only work but to also enable the publisher to thrive at times when other media companies struggle. Most publishers laid off employees during the pandemic, for example, but Dotdash was acquiring more companies.

It is also going to market so much differently than most publishers. It’s hard not to roll our eyes when we hear publishers start their pitch by talking about their *massive* scale – maybe 30 million unique monthly visitors – which is ludicrous when they’re competing against Facebook and its billions of monthly active users. Publishers will also often talk about how great their data is, which, again, sounds ludicrous because they’re still competing against Facebook and also Google, which, for starters, harvests data from more than a billion users with Google accounts and 90% of the world’s search engine use. And so many publishers are still unsure about which advertisers they should be going after, how they can effectively sell programmatically without the internal conflict between direct sales and programmatic, and how to package their inventory in a way that makes sense.

Dotdash is doing none of that. It knows its data and slices its inventory in interesting ways. It lets advertisers buy its inventory simply through any channel they want. It’s not cannibalizing itself between direct sales and programmatic. It’s delivering quality content to users, with a better experience. Through thoughtful packaging it’s also giving something truly unique to its advertisers – a promise many publishers make but fail to live up to.

And it’s working.

One Question

Our one question this week is really three:

With the Meredith deal under its belt, how long will it take before other publishers finally begin trying to replicate Dotdash’s success?

For Dotdash, the Meredith deal is a no-brainer, but what made this such an appealing deal from Meredith’s perspective?

With this deal marrying two distinct types of publishing houses – digital-first and legacy – all publishers must understand which group they belong to: Are you a Dotdash or a Meredith?

Dig Deeper

* Creating a Digital Publishing Leader: the merger announcement deck

Neil Vogel, Dotdash CEO, speaks to Peter Kafka on the Recode podcast about the IAC relationship

Parent company IAC Q2 2020 results

A glimpse at how Dotdash positions itself courtesy of its recent pitch deck

Sara Badler, Dotdash SVP of programmatic revenue (now CRO), on its programmatic strategy

Thanks for reading,

Ana, Maja, and the Sparrow team

Enjoyed this piece? Share it, like it, and send us comments (you can reply to this email).

Who we are: Sparrow Advisers

We’re a results oriented management consultancy bringing deep operational expertise to solve strategic and tactical objectives of companies in and around the ad tech and mar tech space.

Our unique perspective rooted deeply in AdTech, MarTech, SaaS, media, entertainment, commerce, software, technology, and services allows us to accelerate your business from strategy to day-to-day execution.

Founded in 2015 by Ana and Maja Milicevic, principals & industry veterans who combined their product, strategy, sales, marketing, and company scaling chops and built the type of consultancy they wish existed when they were in operational roles at industry-leading adtech, martech, and software companies. Now a global team, Sparrow Advisers help solve the most pressing commercial challenges and connect all the necessary dots across people, process, and technology to simplify paths to revenue from strategic vision down to execution. We believe that expertise with fast-changing, emerging technologies at the crossroads of media, technology, creativity, innovation, and commerce are a differentiator and that every company should have access to wise Sherpas who’ve solved complex cross-sectional problems before. Contact us here.