Epic Games just started a war with a mega drop.

The makers of Fortnite, the biggest game in the world, launched a direct way to buy V-Bucks, the digital currency used in the game. To the buyer/video game player, this looks like a discount: instead of $9.99 you can get the same 1,000 V-Bucks for $7.99 if you make a rather-cool sounding ‘Epic direct payment’ instead of going through the App Store - a 20% savings that Epic is passing directly to the consumer.

And therein lies the rub: that 20% is lower than Apple’s usual 30% app store take rate for in-app payments. It is also against Apple’s terms of service so, quite predictably, within a few hours of launch Apple pulled Fortnite from the App Store.

Epic then filed the lawsuit alleging that Apple and the App Store represent a monopoly:

“Epic is not seeking monetary compensation from this Court for the injuries it has suffered. Nor is Epic seeking favorable treatment for itself, a single company. Instead, Epic is seeking injunctive relief to allow fair competition in these two key markets that directly affect hundreds of millions of consumers and tens of thousands, if not more, of third-party app developers.”

Next came the ad that echoed Apple’s own iconic ‘1984’ ad (back in the day when the monopolists were IBM and Apple was the bright eyed challenger).

Hello, rebels.

Complaints about app store vigs aren’t exactly new. Other large platforms like Facebook, Amazon, Spotify, and Microsoft (who also has an app store) have voiced their displeasure at the payment terms for content over the years - but not too loudly. It’s not an easy task to be vocally critical of a business model when you essentially apply that same platform business model to your own customers (as all these companies do).

Epic is in many ways the perfect challenger to try to change this status quo. Fortnite has a strong console presence and isn’t limited to distribution through app stores alone. It also has the user base: reportedly there are more than 350 million registered user accounts with monthly concurrent players routinely in the tens of millions. While they technically got pulled from both Android and iOS, Android allows relatively easy ways of sideloading content without the Play store. This leaves Apple: if you already have Fortnite installed you can still play. You just can’t download it to a new device (or re-download it since it’s no longer available via the App Store). According to the research firm Sensor Tower, Fortnite was installed 133.2 million times since launching on iOS devices in September 2017, and has produced $1.2 billion in global App Store spending (which would translate to ~$360MM in App Store fees).

Why should you care?

For fledgling app stores launching in the late aughts (Apple’s on July 10, 2008; Google’s on October 22, 2008) the 70/30 revenue split for in-app purchases sounds great. Developers don’t have to front cash unless they’re making revenue, and app store operators can count on the stores to support themselves. Fast forward a decade to 2018: FTC estimates the total value of the US app-based economy at north of $950 billion. Apple’s own analysis of its global app store ecosystem for 2019 estimates the value at $519 billion in billings and sales across the globe.

The current business model is undoubtedly great for Apple. On the surface it may be great for consumers who’ll prioritize ease of use and may not spend too much time (if any) contemplating the inner mechanics of app store monetization or who gets paid for what. It may also continue to work well for small developers who don’t have to worry about incurring additional distribution costs unless there’s revenue coming in. But it increasingly doesn’t work for successful creators who are not solely reliant on app stores for distribution. We’ve seen this play out with large publishers and media properties, too; the app store vig is one of the reasons why you can’t sign up for Netflix through the Netflix app (you sign up and pay via browser, then log in with an already instantiated account).

It’s easy to see why 30% of all in-app transactions seems arbitrarily high: there are only two distribution “competitors” in mobile: Apple and Google. Yes, there are -- technically speaking-- other phone OEM stores out there but they’re, at best, a rounding error rather than a serious competitor/alternative. Apple and Google have little incentive to drive their own take rates down while developers and consumers don’t have any other alternatives. The setup increasingly seems like if your commercial real estate vendor demanded a fraction of your overall revenue instead of annual rent. If the app store is a store, shouldn’t its margins be more in line with single-digit margins of large retailers and not the ~70% (and in some segments estimated at 90%) they’re seeing across services today?

As markets mature they often hit this state when old business models don’t make sense but new ones haven’t emerged yet. We call this the ‘in-between’: a Bermuda triangle of sorts between initial business models that stimulate explosive growth, unit economics, and the models that need to emerge to ensure long-term sustainability.

If the initial business models are versions 1.0, we now know we need versions 2.0 -- but haven’t yet settled on what those should look like.

Consider a few more examples from on-demand land in support of the business model version 2.0 idea:

Uber and Lyft have been hit with a ruling in California that requires them to classify all drivers as employees (for those of you not versed in US employment minutiae, this is a W2 vs a 1099 classification: W2 carries requirements around benefits and protections while the 1099 independent contractor status helpfully has no such demands). Uber in particular has been playing fast and loose with local regulations, often intentionally violating them to gain momentum and customer adoption as a means to pressure local governing bodies into changing the rules in their favor. While the jury is still out on whether or not ridesharing unit economics actually work, ridesharing companies have largely skated past the opportunity to create a system of benefits and support services that fall somewhere between the existing ‘full time employee’ and ‘independent contractor’ categories.

GrubHub, Doordash, Postmates and similar restaurant food delivery tools (yes, UberEats too!) approach charging for their services similarly to app stores: a % of every order. The exact take rate varies: for smaller restaurants it’s 15-30% depending on the service; larger chains typically negotiate these down. That’s not including tips and any applicable delivery fees that go to the person who’s actually delivering your food. This type of setup can be punishing and not sustainable for restaurant operators: while 30% of order value may be a reasonable cost of acquiring a new customer (say someone who found your restaurant through the app) why is it 30% for every subsequent order? Few restaurant patrons would expect apps to work this way. Like with app stores, delivery apps have little incentive to change the economic dynamics for restaurant owners (but at least there’s slightly more competition here).

Classpass and similar services/offer aggregators (going all the way back to Groupon) face a similar challenge: their price point is attractive to consumers yet the premise that they’re discovery platforms that would then lead to consumers buying more services from individual vendors is fundamentally flawed. Consumers stick to the apps because of ease of use and optionality: why buy 10 classes directly from a yoga studio when you can keep sampling through the app with less commercial commitment? If you’re failing on the ‘bring new profitable customers’ part of the value proposition, what else can you bring to the table that supports a sustainable ecosystem?

Unsurprisingly digital advertising is also in a state of transition: both from a business model perspective and a purely technical one. On the business model side, we’ve seen platforms (Facebook, Google, and whoever is running third in your market) capture the bulk of the share of ad spend, while traditionally strong advertising categories like TV and sports advertising dwindle (both severely impacted by the pandemic). The open internet is now a mere ~30% of all spend. On the technology side we’re anticipating the third-party cookie apocalypse and reacting to IDFA changes/deprecation while trying to assemble a system that mirrors the targeting and attribution capabilities of walled gardens with some duct tape and a lot of mentions of AI, ML, and fancy data science. Consumers are also tired of us and shifting their content consumption patterns to ad-free realms of SVOD, other subscriptions, ad blockers, and general indifference (until a meticulously cut Nike ad comes along, or the aforementioned Fortnite call to arms).

Enough with the problems.

What’s the solution?

Some of the core tenets that the 2.0 models and the new commercial stacks that need to embrace are:

Sustainability: The pricing model that works to get a service off the ground isn’t necessarily the best fit as that service reaches maturity. We’re well past the days of app stores and mobile services being the new kid on the block and the commercial models need to grow up too. This challenge reminds us of the early days of SaaS when a pay-by-usage model became a much better deal than large, non-burstable, on-premise deployments. SaaS may be the (perhaps interim) solution here, too: if we think of the app store or other distribution/marketplace apps primarily as service providers, then a SaaS model with tiers and caps readily comes to mind. Instead of charging a flat rev share or % of every transaction, perhaps after a minimum monthly threshold the model progressively adapts to a lower take rate. Creators and operators keep more of their success; distributors still keep healthy margins; customers continue to enjoy easily accessible services.

Flexibility: Epic has a full-blown economy inside and adjacent to Fortnite. Other virtual worlds like Animal Crossing do, too. Restaurants need other services in addition to online ordering. A new back office stack around creators and operators is emerging: consider Substack’s suite of commercial services for newsletter authors, the Toast app that provides back office/back of house services in addition to online and contactless ordering for restaurants, bars, and clubs, or Bandcamp that’s creating tools for building direct relationships between musicians and their fans. Each of these mainly vertical sub-ecosystems is emerging in response to the need for better commercial arrangements than in the mainstream system; within each, rather than a fixed platform take rate, there’s room for modularity, flexibility, and configuring the right support ecosystem each individual business needs.

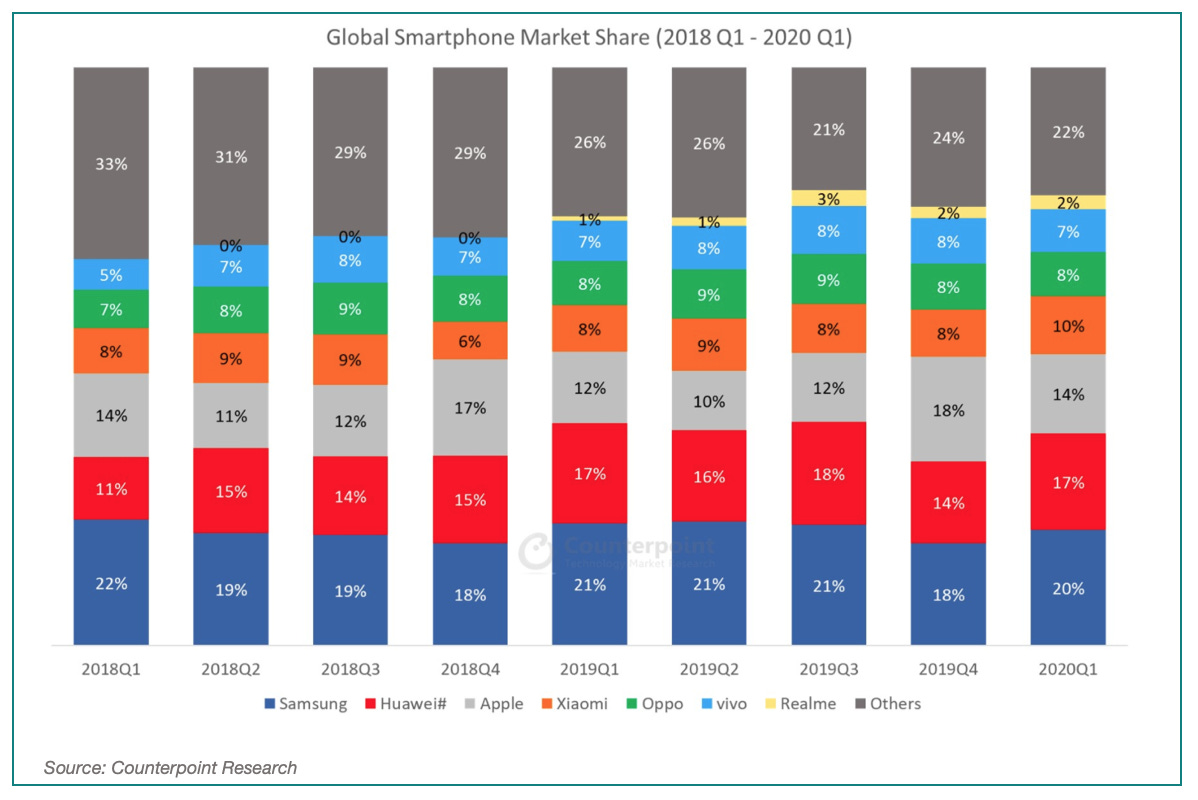

Competition: Today’s app ecosystem begs the question if a marketplace can truly be efficient if there are only two options/competitors available (Apple and Google). This concept will surely resonate with a variety of antitrust regulators who are trying to wrap their heads and outdated legislation around today’s platforms. What if more competitors entered the ring? Looking at this global split of smartphone market share, courtesy of Counterpoint Research, that doesn’t seem to be entirely out of the realm of the possible for someone like Samsung or Huawei:

Epic Games kicked off a generational shift that challenges the very first principles of commercializing apps and digital content. The timing and subsequent campaign could not have been selected or executed better. It’s fitting that Epic used Apple’s iconic 1984 ad to fire the opening salvo: theirs is a rallying cry for a new generation of “the crazy ones, the misfits, the rebels, the troublemakers, the round pegs in the square holes ... the ones who see things differently”, ready to replace the incumbents.

One question:

The dominant means of financing and funding hyper growth and Versions 1.0 was venture - and it carried along expectations of venture-sized returns for every service. What will the dominant model that funds and fuels Versions 2.0 be?

Dig deeper:

The two lawsuits:

Epic v Google (note the filename: “Project Liberty”)

The rebellion grows

Counterpoint Research’s smartphone share analysis

Each week we curate a selection of the most interesting (free) events in adtech, martech and friends - check it out here.

Enjoyed this piece? Share it, like it, and send us comments (you can reply to this email).

Who we are: Sparrow Advisers

We’re a results oriented management consultancy bringing deep operational expertise to solve strategic and tactical objectives of companies in and around the ad tech and mar tech space.

Our unique perspective rooted deeply in AdTech, MarTech, SaaS, media, entertainment, commerce, software, technology, and services allows us to accelerate your business from strategy to day-to-day execution.

Founded in 2015 by Ana and Maja Milicevic, principals & industry veterans who combined their product, strategy, sales, marketing, and company scaling chops and built the type of consultancy they wish existed when they were in operational roles at industry-leading adtech, martech, and software companies. Now a global team, Sparrow Advisers help solve the most pressing commercial challenges and connect all the necessary dots across people, process, and technology to simplify paths to revenue from strategic vision down to execution. We believe that expertise with fast-changing, emerging technologies at the crossroads of media, technology, creativity, innovation, and commerce are a differentiator and that every company should have access to wise Sherpas who’ve solved complex cross-sectional problems before. Contact us here.